Full version - shortened article published by the German Society for Time Policy, Zeitpolitisches Magazin No. 36 July 2020 (ISSN 2196-0356, download here).

"We stand up for people's safety and provide help around the clock."1Bavarian State Ministry of the Interior, Leitbild der Bayer. Polizei - Handlungs- und Orientierungsrahmen für die Zukunft, https://www.polizei.bayern.de/wir/leitbild/index.html/3249, accessed on 01.03.2020

This quote from the mission statement of the Bavarian Police undoubtedly applies to all police authorities - they guarantee security in a society around the clock. Although the work is 24/7224/7 stands for 24 hours, 7 days a week, i.e. the provision of work every day at any time. This is not a unique feature of police work, as around one in six employees in Germany works shifts (Radtke 2020), but it is characteristic of police work. In order to understand the (time) organization of police work and its impact on public safety, it is also necessary to understand the effects that shift work, which is necessary to ensure the constant availability of the police, has on people. Even if some police working time organizers do not seem to take this into account, police officers are also human beings and the organization of shift work has a significant influence on their ability to perform and act and thus directly on (in)security in public spaces.

- Organization of working hours

Fundamentals of ergonomics

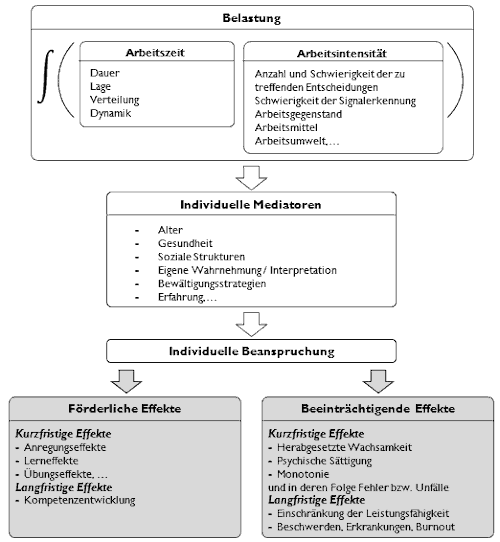

The effect of shift work on people can be clearly explained using the stress-strain model (see Figure 1). The first component of this model to be considered is stress. It is a function of the work intensity (combination of all influences acting on people at work) and the working hours. There is a multiplicative relationship between intensity and duration of stress (Rutenfranz et al.; Janßen and Nachreiner 2004; Schmidtke and Bubb 1993). Accordingly, heavier work over a shorter period of time can lead to the same level of stress as lighter work over a longer period of time (Wirtz, 2010).

This stress is mediated by individual mediators and leads to a specific strain for each person. With regard to shift work, for example, age plays a decisive role as a mediator. A large number of studies have shown an increase in the negative effects of shift work on health from the age of 40 to 50 (Knauth and Hornberger 1997). The strain placed on the individual can lead to positive effects, such as learning or activation processes. However, it can also have negative effects, such as mental fatigue or reduced alertness. If an individual's workload is too high over the long term, it poses health risks (Morschhäuser et al. 2014; DIN EN ISO 10075-1 2018).

Based on this model, the effects of police work organization on safety in public spaces will be explained in further explanations. However, an initial examination of the model should already have made one central adjustment screw clear - the employer has a central influence on the workload through the function of working time organization.

Work intensity

In order to assess the stress of police work, it is also necessary to assess the intensity of police work. However, this proves to be quite challenging, as the intensity varies from station to station, from weekday to weekday and from hour to hour. Although patterns can certainly be found in the time variations, these are usually specific to a particular department (Bürger 2015; Bürger and Nachreiner 2019). In order to approximate a certain baseline of intensity, the police task description provides an initial point of reference: the police are responsible for averting and eliminating dangers of all kinds, ensuring the protection of all citizens and providing assistance, recording traffic accidents, regulating and monitoring road traffic, prosecuting and investigating criminal offenses (Bayerische Polizei - Aufgaben 2020). This clearly shows the variety of tasks to be performed, which implicitly also indicates significant differences in workload both between and within the individual fields of activity. For example, in terms of stress assessment, there is a clear difference between having to record a traffic accident in sunshine or hail showers, whether the people involved are uninjured or whether body parts are scattered at the scene of the accident. Whether you are taking photos of evidence in the pursuit of a crime or chasing a knife offender on foot in the dark. Police officers on guard duty and rotating shifts, as shift work on patrol duty is called in the police force, are the ones who have to master the full range of activities, at least until specialists arrive. Numerous studies on the work intensity of these shift workers consistently show a high level of psychological stress, for example when dealing with victims or children, in the case of outstanding and serious crimes or when required to resolve complex situations. There are also reports of high demands from superiors and the public, while officers are also exposed to disrespect and insults (Bürger and Nachreiner 2018; Jain and Stephan 2000; Violanti 2014a; Klemisch 2006; Wiendieck et al. 2002; Schmucker 2017).

But the physical burden should not be underestimated either. The equipment (radio, weapon belt, weapon, spare magazine, handcuffs, baton, bullet-resistant vest, etc.) weighs around 6 kilograms (Biewald and Heyl 2020) and must be carried with every step, when getting in and out of vehicles. On-call police officers carry an additional 22 kilograms during large-scale operations (Buntrock and Hasselmann 2020). The bullet-resistant vest is also not breathable and easily causes heat build-up. In addition, police officers are regularly exposed to hazardous substances, be it bacteria or viruses (infectious diseases) during contact with people and animals or dangerous gases, for example during operations or during shooting training (Violanti 2014b).

Ultimately, it can be concluded that the police service is characterized by a not inconsiderable physical intensity and a high level of psychological stress, although the extent of this is subject to upward fluctuations.

Working hours

However, as the stress and strain model makes clear, the factor of working time must also be considered when assessing stress. First of all, it is clear that people absolutely need breaks in order to regenerate and avoid the short-term consequences of overexertion (e.g. perception and concentration errors). Accordingly, numerous studies show that the risk of accidents generally decreases noticeably after a break (Deloitte 2010; Spencer et al. 2006; Tucker et al. 2003). The frequency, timing and length of the required breaks depend in particular on the duration and intensity of work (and their interactions), as can also be deduced from the stress-strain model. As a rule, no fixed breaks or break times are provided for civil servants on guard and rotating shift duty, but they can generally use times without assignments or other necessary activities for short regeneration breaks. However, a study by Bürger (2019), for example, shows that around 1/3 of the more than 900 civil servants surveyed are rarely or almost never able to take breaks that they subjectively perceive as sufficient.

However, the length and location of working hours must also be examined more closely. In summary, it can be stated that the risk of accidents increases exponentially after the eighth or ninth hour of work (Wirtz 2010). On the basis of their meta-study, Spencer et al. (2006) came to the conclusion that a twelve-hour shift has a 27.5% higher accident risk than an eight-hour shift. If the risk is not considered in relation to the entire shift duration, but to the working hour, it can be seen that the twelfth hour carries twice as high a risk as the average of the first to eighth hours. These findings are also underpinned by the results of the quasi-experiment conducted by Bell, Virden, Lewis, & Cassidy (2015) on behalf of the Phoenix Police Department. Here, the duty time at one of two comparable departments was increased from 10 to 13 hours. In addition to the significant negative effects of the longer working hours on the ability to concentrate, react and the general quality of life, another result of the study is also worthy of note: the number of serious citizen complaints that had to be punished with disciplinary measures increased significantly with the longer working hours.

In addition to the duration of work, the location of working hours also plays an important role. Humans are diurnal creatures and, in terms of all bodily functions, are not designed to perform at night, but to sleep (Bürger 2015). Consequently, the significant increase in the risk of accidents at night is not surprising. Compared to the morning shift, afternoon shifts have a higher accident risk of around 15% and night shifts a higher risk of 27% (Spencer et al., 2006). When looking at the course of the day, the risk of accidents increases significantly from 6 p.m. and peaks in the late night hours (approx. 2 a.m.) (ibid.). However, studies show that it is precisely during night shifts that officers have by far the highest fatigue levels and at the same time have to complete the subjectively and often objectively most dangerous assignments (Bürger and Nachreiner 2019; Violanti et al. 2013). "The combination of "night work plus long shifts" or situations involving public safety are of course particularly critical" ( Knauth and Hornberger 1997, p. 46).

The combination of work intensity and working hours must be taken into account. If you want professional safety in public spaces for citizens, but also for the officers on duty, you have to reconcile these factors. Or as §§ 3 to 5 of the ArbSchG put it: the employer must assess the risks arising from work processes, working hours and their interaction and minimize the resulting hazards for employees. In view of the occupational science findings briefly outlined above, it can only be concluded that shift lengths in excess of 8 hours can only be permissible after careful consideration of the individual case.3The statements in the relevant literature on the duration of working hours are clear: "An extension of eight-hour shifts should be avoided at all costs in the event of: high mental or physical stress during work, additional overtime, high risk in the event of misconduct, understaffing [...]" ( Beermann 2010, p. 10). On the other hand, night shifts of up to 12 hours are often permitted or even common in police guard and shift work. These ergonomic findings on the humane organization of shift work outlined above4§Section 6 (1) ArbZG (Working Hours Act of June 6, 1994 (BGBl. I p. 1170, 1171), which was last amended by Article 12a of the Act of November 11, 2016 (BGBl. I p. 2500)): "The working hours of night and shift workers shall be determined in accordance with established ergonomic findings on the humane organization of work". However, the ArbZG does not apply directly to civil servants.are also used by courts, for example, when assessing whether an employer has fulfilled its obligations under the German Occupational Health and Safety Act (ArbSchG). Those who order or allow gross deviations from these long-published and publicly accessible findings should be aware that the Occupational Health and Safety Act establishes a guarantor obligation in accordance with Section 13 of the German Criminal Code (StGB). For example, a traffic accident involving a patrol on duty at five o'clock in the morning towards the end of a ten- or even twelve-hour night shift, in which fatigue could have played a role as a cause, could also result in those who ordered or tolerated these working hours being charged with assault in office (possibly by omission).

Consequences of overloading

The short-term overloads described so far therefore endanger safety in public spaces in two ways: on the one hand with regard to the quality of safety provision and on the other hand with regard to the risk of accidents and the associated danger to themselves and others. At the same time, it should not be forgotten that it is essential for safety in public spaces that officers have their full ability to perceive, process and react and are not limited by overwork. There is no doubt that the situations in which the police are needed require appropriate solutions to problems on the one hand, but also lightning-fast reactions on the other, which can make the difference between life and death.

However, the long-term consequences of overwork can also have an impact on (in)security in public spaces, namely when too few officers are available due to illness. The available research data on long-term overuse paints a clear picture here. Police officers who work round the clock on guard and rotating shifts to provide security work against their circadian and therefore metabolic daily and weekly rhythms. As a result, shift work entails a significantly increased risk of specific illnesses. These include sleep disorders in particular, but also appetite disorders, gastrointestinal complaints, cardiovascular diseases, musculoskeletal disorders and psychovegetative disorders (Becker et al. 2009; Bürger and Nachreiner 2019; Boggild and Knutsson 1999; Nachreiner et al. 1981; Knutsson 2003). These illnesses usually lead to a limited ability to work or an inability to work at night (Hartley et al. 2014; Zimmerman 2014; Nachreiner et al. 2009). Police officers in particular have long had an above-average number of sick days (Bürger 2015; Kopietz 2014; SVZ.de 2014). They have a high risk of illnesses typical of shift work and the associated service restrictions (Nachreiner et al. 2009). This is despite the fact that the police population should be particularly healthy compared to other occupational groups (so-called "healthy workers") due to the medical check-ups carried out when recruiting police officers. However, mental illness is also not uncommon among police officers, with at least 15% of respondents complaining of emotional exhaustion, burnout, anxiety disorders or depression, depending on the study (Bürger and Nachreiner 2019; Kopietz 2014; Wiendieck et al. 2002). Some of the studies attribute this to the intensity of the police profession, but also to the inner tension of the officers, who have chosen the profession predominantly out of conviction and are committed to it, but experience little appreciation. These mental illnesses in particular should be given special attention with regard to practical police work, because chronic fatigue, inner restlessness, nervousness, depression, anxiety and irritability are symptoms that may not be immediately diagnosable for superiors, but are undoubtedly not compatible with the self-image of professional police work.

Social participation

To conclude the area of working time organization, it is necessary to mention the third classic risk of shift workers: limited social participation. Our society is an after-work and weekend society. Social activities take place after "normal" working hours, i.e. in the evening and at weekends. It is therefore important to be able to use these periods as often as possible for social participation and social engagement (Neuloh 1964). Numerous studies show corresponding cuts in social life for shift workers, especially in the police (e.g. Knauth and Hornberger 1997; Nachreiner et al. 1981; Nachreiner 2011; FOWIG 1994; Bürger and Nachreiner 2019). So if you follow the recommendations of occupational science and take occupational safety seriously for police officers too, you would have to set the maximum shift length at 8 hours. However, with, for example, 40 hours to be worked per week, this means that employees would have to work five shifts per week. The remaining two possible days off per week would also regularly be significantly restricted in their leisure value by a previous night shift. Given the atypical nature of shift work, this means that social life is ultimately reduced to zero in an unacceptable way. All in all, there is only one logical conclusion: a stress-adequate and socially acceptable weekly working time in shift work. This should be achieved by replacing the financial compensation for shift work (which cannot reduce the risks of shift work) with time compensation. If shift work alone is taken as a stress factor, the weekly working hours of shift workers would have to be reduced by 16.5 hours for a 40-hour week in order to ensure the same level of health impairment as for non-shift workers (Nachreiner and Arlinghaus 2013). This seems utopian, but illustrates the differences that would actually be necessary. However, in order to tackle the basic problem, i.e. to increase occupational safety, reduce the long-term consequences of the obviously widespread overload and at the same time enable a social life, a weekly working time of 35 hours could make a decisive contribution as a first approach, for example in the form of a factorization of working time at times that are socially detrimental and harmful to health (Bürger 2015; Bürger and Nachreiner 2019).

- Work organization

However, it is not only the organization of working hours in the narrower sense that plays a central role with regard to (in)security in public spaces; the organization of work must also be considered. This involves answering the question of how many police are needed at what time to ensure safety. It is possible to calculate this and plan for appropriate reserves thanks to the precise recording of emergency calls and incidents. However, this is of course only based on the objective security situation, but it should nevertheless be made mandatory. On the one hand, because every officer who is called out at times that are socially useful or harmful to health5Proposal for definition from Bürger and Nachreiner 2019: health-impairing times (daily from 02:00 to 06:00) and socially impairing times (Monday to Friday from 18:00 to 02:00 and Saturday and Sunday from 06:00 to 02:00), each of which could be factorized to different degrees. work, even though this is not objectively necessary. Secondly, of course, for cost reasons, because every hour of duty costs taxpayers' money. Many police forces have already adopted precisely this approach and introduced so-called "demand-oriented shift models".6Unfortunately, this somewhat misleading term is used for this type of shift work arrangement, particularly in northern Germany, implying that it is only possible to work according to demand in this model. However, this is also possible with fixed shift groups if the shift times are adjusted accordingly (Bürger 2015).or "flex models" have also been introduced. Here, there are no fixed shift groups, but an empty duty roster is issued in advance with the number of staff required, e.g. Saturday afternoon shift five officers, Saturday night shift seven officers. The officers are then free to sign in and work alternately with different colleagues and supervisors. However, this trend towards flexibilization also harbours risks. Fixed shift groups form a strong social structure, with colleagues supporting each other when problems arise or when dealing with difficult or even traumatic events. In addition, there is a manager directly responsible for this group who meets regularly with their employees, looks after them (care) but also exercises control, for example with regard to the quality of work, dealings with citizens and, if necessary, intervenes to direct them. In groups that are constantly being thrown together without fixed responsibilities, the development of a social structure, mutual interest, but also the effect and understanding of leadership is significantly lower (Bürger 2015; Bürger and Nachreiner 2018). However, a healthy social fabric seems essential, especially in the police profession, which is characterized by emotional stress. The same applies to the need for effective leadership, on the one hand out of care for employees, but also to protect the organization from black sheep or police officers who stray from the right path. In order to ensure professional security in public spaces, the organization of work should therefore be very consciously and deliberately made more flexible and individualized.

- Summary

How work (time) organization in the police can be designed in order to optimally guarantee public safety (and implicitly also occupational safety for police officers) can be summarized as follows:

- As a general rule, the daily working hours for guard and shift work should not exceed 8 hours in order to ensure occupational safety and the quality of the service.

- The weekly working hours should correspond to the workload. Consequently, services at times that are socially or health-related stressful should be factored into the calculation of working hours so that, for example, a weekly working time of 35 hours is not exceeded for those working exclusively in shifts. This is the only way to avoid occupational safety and the long-term consequences of overwork and at the same time give civil servants the opportunity to participate in general social life, at least to a limited extent.

- Only as many civil servants as are absolutely necessary should be on duty at times that are socially disruptive and harmful to health.

The time/shift allocation of officers should only be made more flexible and individualized to the extent that effective leadership and a social structure within the group continues to be guaranteed. This is essential for the welfare of individual employees, but also for the functioning of a police force based on the rule of law.

Bibliography

Bavarian Police - Tasks (2020). Available online at https://www.polizei.bayern.de/wir/aufgaben/, last updated on 20.03.2020, last checked on 20.03.2020.

Becker, H. F.; Ficker, J.; Fietze, I.; Geisler, P.; Happe, S. (2009): S3 guideline. In: Somnology 13 (S1), pp. 1-160. DOI: 10.1007/s11818-009-0430-8.

Beermann, B. (2010): Night and shift work. In: B. Badura, H. Schröder, J. Klose and K. Macco (eds.): Fehlzeitenreport 2009. Arbeit und Psyche: Belastungen reduzieren - Wohlbefinden fördern. Berlin, pp. 71-82.

Bell, Leonard B.; Virden, Thomas B.; Lewis, Deborah J.; Cassidy, Barry A. (2015): Effects of 13-Hour 20-Minute Work Shifts on Law Enforcement Officers' Sleep, Cognitive Abilities, Health, Quality of Life, and Work Performance. In: Police Quarterly 18 (3), pp. 293-337. DOI: 10.1177/1098611115584910.

Biewald, Nicole; Heyl, Marcus (2020): Germany your police - equipment, units and weapons - News in Germany - Bild.de. Available online at https://www.bild.de/news/inland/polizei/die-einheiten-ausruestungen-und-waffen-41369432.bild.html, last updated on 03.05.2020, last checked on 03.05.2020.

Boggild, H.; Knutsson, A. (1999): Shift work, risk factors and cardiovascular disease. In: Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health 25 (2), pp. 85-99.

Buntrock, Tanja; Hasselmann, Jörn (2020): 22 Kilo Mehrgewicht: Wie Berlins Polizei für den 1. Mai waffnet. Available online at https://www.tagesspiegel.de/berlin/schwere-polizeiausruestung-am-1-mai-in-berlin-mit-22-kilo-mehrgewicht-auf-die-strasse/9818108.html, last updated on 03.05.2020, last checked on 03.05.2020.

Bürger, B.; Nachreiner, F. (2019): Findings on stress and strain in police guard and rotating shift duty. Initial situation, consequences and need for action. In: Andrea Fischbach and P. Lichtenthaler (eds.): Healthier living in the police. Frankfurt a. M.

Bürger, Bernd (2015): Working time models for the police patrol service. An interdisciplinary analysis using the example of the Bavarian police. Frankfurt am Main: Verl. für Polizeiwiss.

Bürger, Bernd; Nachreiner, Friedhelm (2018): Individual and organizational consequences of employee-determined flexibility in shift schedules of police patrols. In: Police Practice and Research 19 (3), pp. 284-303. DOI: 10.1080/15614263.2017.1419130.

Deloitte (2010): Study to support an Impact Assessment on further action at European level regarding Directive 2003/88/EC and the evolution of working time organization. Brussels.

DIN EN ISO 10075-1 (2018): Ergonomic principles related to mental workload - Part 1: General aspects and concepts and terminology (ISO 10075-1:2018); German version EN ISO 10075-1:2018. Berlin.

FOWIG (1994): Results of the opinion survey of the Bavarian police. (not published).

Hartley, Tara A.; Fekedulegn, Desta; Burchfiel, Cecil M.; Mnatsakanova, A.; Andrew, Michael E.; Violanti, John M. (2014): Health Disparities Among Police Officers. In: John M. Violanti (ed.): Dying for the job. Police work exposure and health. Springfield, Il, pp. 21-40.

Jain, Anita; Stephan, Egon (2000): Stress in patrol duty. How stressed are police officers? Berlin: Logos-Verl.

Janßen, Daniela; Nachreiner, Friedhelm (2004): Flexible working hours. In: Series of publications of the Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health / Research (Fb 1025). Bremerhaven: Wirtschaftsverl. NW, Publ. for New Wiss.

Klemisch, Dagmar (2006): Psychosocial stress and stress management of police officers. Münster, last reviewed on 30.04.2017.

Knauth, P.; Hornberger, S. (1997): Shift work and night work. Problems - Forms - Recommendations. 4th ed. Munich.

Knutsson, A. (2003): Health disorders of shift workers. In: Occupational Medicine 53, pp. 103-108.

Kopietz, Andreas (2014): Health study by the Free University of Berlin. Duty makes Berlin police officers ill. Published by Berliner Zeitung. Available online at http://www.berliner-zeitung.de/103084, last checked on 05.05.2017.

Morschhäuser, M.; Beck, D.; Lohmann-Haislah, A. (2014): Mental stress as a subject of risk assessment. In: Federal Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (ed.): Gefährdungsbeurteilung psychischer Belastung. Experiences and recommendations. Berlin: Schmidt, pp. 19-44.

Nachreiner, F. (2011): Working time as a risk factor for safety, health and social participation. In: Gesellschaft für Arbeitswissenschaft e. V. (ed.): Neue Konzepte zur Arbeitszeit und Arbeitsorganisation. Proceedings of the 2011 Fall Conference of the Society for Ergonomics. Dortmund, pp. 15-32.

Nachreiner, F.; Arlinghaus, A. (2013): On the temporal compensation of stress due to unusual working hours. In: Gesellschaft für Arbeitswissenschaft e. V. (ed.): Chancen durch Arbeits-, Produkt- und Systemgestaltung - Zukunftsfähigkeit für Produktions- und Dienstleistungsunternehmen. Dortmund, pp. 569-572. Available online at http://www.gawo-ev.de/cms2/uploads/KompensationRV3.pdf?phpMyAdmin=8b6ed5803bbabc8d5f96599c9c6997ad.

Nachreiner, F.; Rohmert, W.; Rutenfranz, J. (1981): Gutachterliche Stellungnahme zum Problem des Wechselschichtdienstes bei der Polizei (not published).

Nachreiner, F.; Wirtz, A.; Browatzki, Daniela; Giebel, Ole; Schomann, C. (2009): Working life of police officers - results of a pilot study. Oldenburg. Available online at http://www.gdp-bremerhaven.de/mediapool/86/864657/data/Machbarkeitsstudie_Verlaengerung_Lebensarbeitszeit.pdf.

Neuloh, Otto (1964): Socialization and shift work. In: Social World 15 (1), pp. 50-70.

Radtke, Rainer (2020): Shift work - proportion of the working population in Germany by 2018 | Statista. Available online at https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/360921/umfrage/anteil-der-erwerbstaetigen-in-deutschland-die-schichtarbeit-leisten/, last updated on 01.03.2020, last checked on 01.03.2020.

Rohmert, W. (1983): Forms of human labor. In: W. Rohmert and J. Rutenfranz (eds.): Praktische Arbeitsphysiologie. Stuttgart, New York, NY, pp. 5-29.

Rohmert, W. (1984): The stress-strain concept. In: Journal of Ergonomics 38 (4), pp. 193-200.

Rutenfranz, J.; Knauth, P.; Nachreiner, F.: Arbeitszeitgestaltung. In:, pp. 459-599.

Schmidtke, H.; Bubb, H. (1993): The stress-strain concept. In: H. Schmidtke (ed.): Ergonomics. Vienna, pp. 116-120.

Schmucker, R. (2017): Emotional stress in the police profession. How common are conflicts and disrespectful treatment? Berlin (DGB-Index Gute Arbeit kompakt).

Spencer, M.; Robertson, K.; Folkard, S. (2006): The development of a fatigue / risk index for shiftworkers. Ed. by Health and Safety Executive. Available online at http://www.hse.gov.uk/research/rrpdf/rr446.pdf, last checked on 03.04.2014.

SVZ.de (2014): Police officers increasingly sick. 36.7 DAYS OFF. Available online at http://www.svz.de/regionales/mecklenburg-vorpommern/polizisten-immer-oefter-krank-id7751326.html, last checked on 05.05.2017.

Tucker, P.; Folkard, S.; Macdonald, I. (2003): Rest breaks reduce accident risk. In: The Lancet 361, p. 680.

Violanti, John M. (ed.) (2014a): Dying for the job. Police work exposure and health. Springfield, Il.

Violanti, John M. (2014b): Hazardous Exposures in Law Enforcement. In: John M. Violanti (ed.): Dying for the job. Police work exposure and health. Springfield, Il, pp. 4-20.

Violanti, John M.; Fekedulegn, Desta; Andrew, Michael E.; Charles, Luenda E.; Hartley, Tara A.; Vila, Bryan; Burchfiel, Cecil M. (2013): Shift work and long-term injury among police officers. In: Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health 39 (4), pp. 361-368. DOI: 10.5271/sjweh.3342.

Wiendieck, G.; Kattenbach, R.; Schönhoff, T.; Wiendieck, J. (2002): POLIS. Police in the mirror. Cologne.

Wirtz, A. (2010): Health and social effects of long working hours. Dortmund, Berlin, Dresden. Available online at http://d-nb.info/1029472718/34.

Zimmerman, F. (2014): Cardiovascular Risk in Law Enforcement. In: John M. Violanti (ed.): Dying for the job. Police work exposure and health. Springfield, IL, pp. 41-56.